Mercury is a naturally occurring element in the environment, originating from volcanic eruptions, geological erosion, and forest fires — but even at low levels, it can be highly toxic.

Human activities now contribute significantly to the presence of mercury in the atmosphere, with major sources including coal burning, mining, metal smelting and refining, and the incineration of municipal, industrial, and medical waste. As these activities have become more widespread, the concentration of atmospheric mercury has nearly doubled since the Industrial Revolution.

Once converted into methylmercury — a form that builds up in animals and magnifies through food chains — it can cause considerable reproductive and neurological disorders (Philibert et al., 2022). Additionally, mercury tends to accumulate in the Arctic even though its sources are far away. This poses significant risks to our northern communities and is one of the main reasons it is studied in Alert.

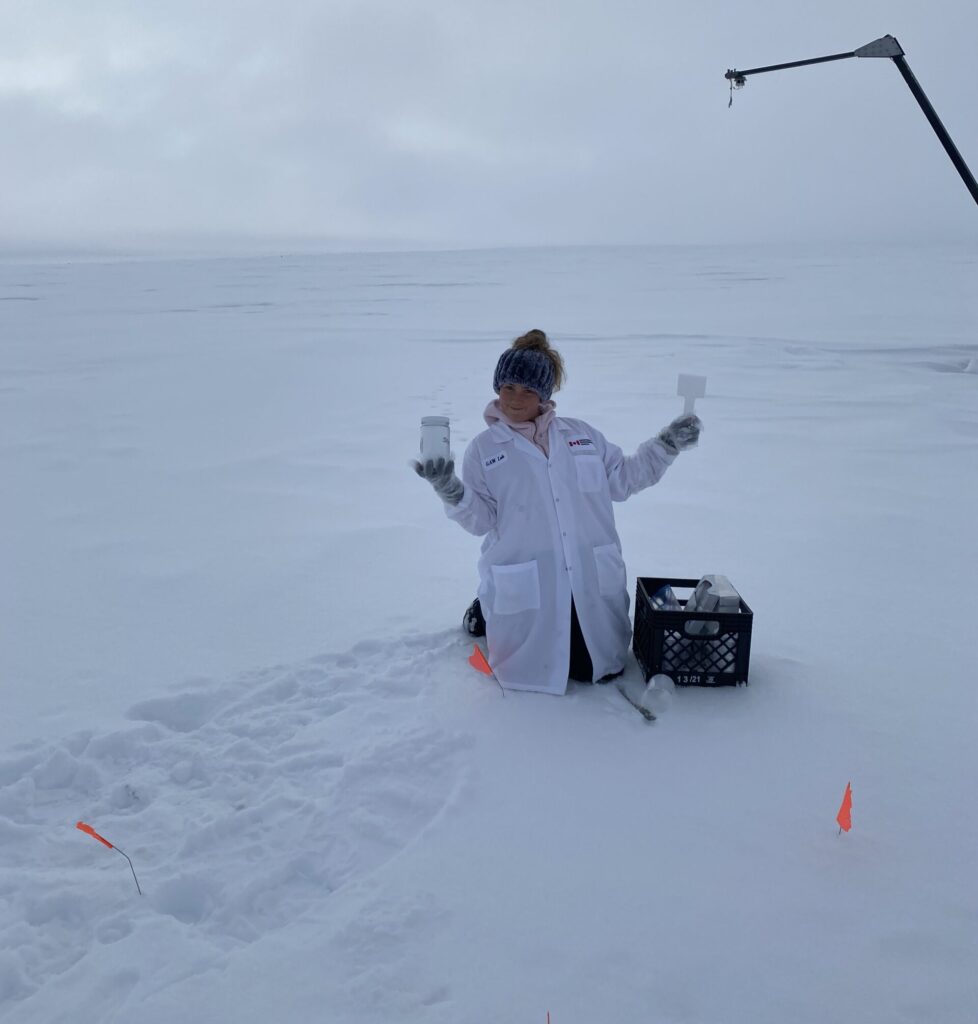

Here at the GAW lab, we monitor atmospheric mercury on behalf of the Northern Contaminants Program (a Canadian program that studies the effects of long-lived, toxic pollutants on our Northern communities). ‘Monitoring’ involves more than just sampling the air above the lab. We also collect mercury from snow, ice, and sometimes permafrost. Funny that we collect atmospheric mercury from these ground locations?

One interesting thing about the mercury program in Alert is the discovery of Atmospheric Mercury Depletion Events (more commonly referred to as ‘depletion events’). Depletion events may sound like a good thing; however, it is simply the process of converting mercury into a form that no longer pollutes the atmosphere, but rather terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Depletion events have helped scientists understand mercury cycling on a global scale, and they were discovered right here in Alert (Steffen et al., 2008)!

Here is a little breakdown of how it works: during the dark season, there is no sunlight to initiate any reactions with atmospheric mercury. Because of this, mercury accumulates in Alert over the winter months. By the end of the dark season (late Feb – early March), we expect to have (on average) atmospheric mercury concentrations of ~50ng/m³. To compare, today (July 21, 2025), our analyzers measured 1.568 ng/m³. During polar sunrise, bromides are released from the surface of sea ice and react with the accumulated atmospheric mercury. This reaction transforms mercury into a heavier, more reactive, and water-soluble form of mercury that can settle out of the air and onto the sea ice and snow.

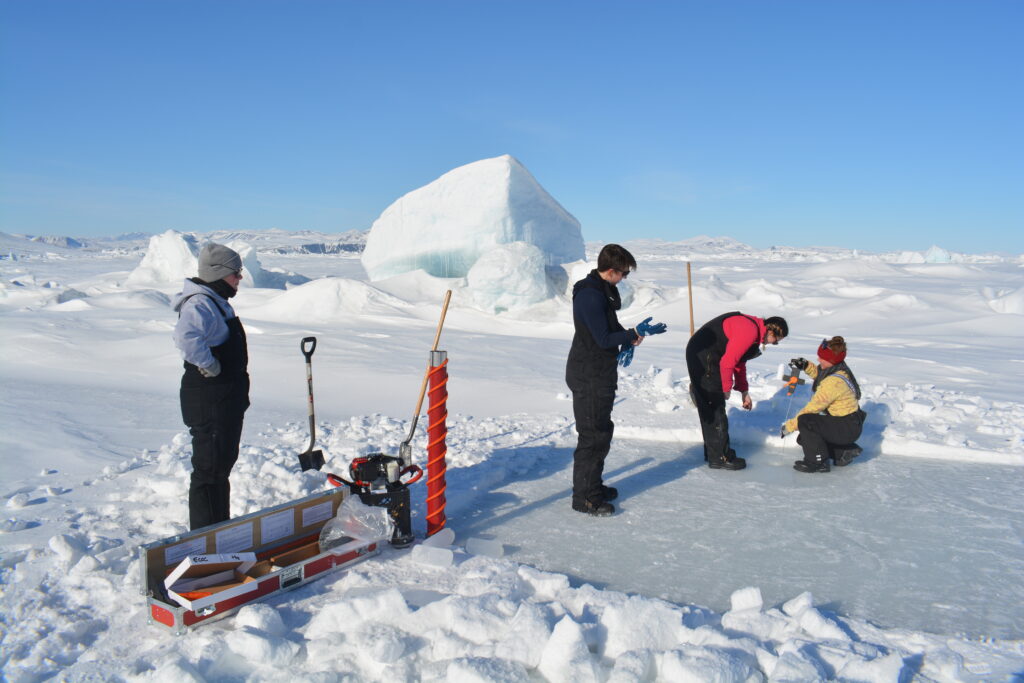

Following this discovery, we now collect ice cores and snow samples to try to quantify these depletion events in the spring=) Just as a side note, the ice cores we collected from the multiyear ice in 2024 were 4.5m deep! This gives our scientists years’ worth of mercury data!

Sources

Steffen, A., Douglas, T., Amyot, M., Ariya, P., Aspmo, K., Berg, T., … & Temme, C. (2008). A synthesis of atmospheric mercury depletion event chemistry in the atmosphere and snow. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 8(6), 1445-1482.

Philibert, A., Fillion, M., Da Silva, J., Lena, T. S., & Mergler, D. (2022). Past mercury exposure and current symptoms of nervous system dysfunction in adults of a First Nation community (Canada). Environmental Health, 21(1), 34.

** A good read on what our mercury scientists are up to in addition to their research in Alet 😀